Susan: You made a film about the Greek Goddess Circe. What about the myth and character of Circe drew you to her as subject matter?

Lenore: All of my projects engage history in some way. History is a fictional construction. Narratives cross cultural lines, events happen that make no sense and myths codify them. They persist in deep time. I’m interested in these long running narratives and their shifting representations in art and film. Circe was a perfect subject for this kind of exploration. There are hundreds of representations of her over the millennia, but after Homer most are deeply sexist. In my comedy, Circe, all this is reversed. As for an interest in antiquity it extends back to childhood. As a girl I wandered through the corridors of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine artifacts (acquired shamefully as we now know). It’s the collective unconscious and you never forget it. And later In grad school I analyzed Greek sculptural fragments, Gods and Goddesses, to determine the workshops where they are made.

In the Odyssey, Book 10, Circe’s affinity with ancient Goddess religions is clear. Her sexuality is connected to the fertility of animals and plants. She lives alone in a stone house on an island Aeaea with lions and wolves, relationships glimpsed in stele dating from c. 3000 B.C., where unnamed Goddesses are shown in relief flanked by lions and wolves.

After Homer, since the fifth century B.C., Circe has been eroticized and reviled in art and literature as an sexual enslaver of men in works by male authors and artists, among them: Hesoid, Ovid, Virgil, Spenser, Milton, Calderon and in illustrations from Boccaccio’s Concerning Famous Women to paintings by John Waterhouse. Adhering to emerging patriarchy this goddess was deprived of her divinity and viewed as a personification of passion and vice. Myth persists while attitudes change. Circe has since been radically re-envisioned by Miller, by Margaret Atwood in Mud Poems: You Are Happy, by Toni Morrison in Song of Solomon, by Judith Yarnall in Transformations of Circe.

Susan: Is there a particular feminist component to the Homeric incarnation of Circe?

Lenore: She’s at the edge of the world, an equal to Odysseus, a benevolent shapeshifter. She guides Odysseus and his men on their journey to the underworld and survives with her powers undiminished. Beyond that, the reader recognizes that her body, a female body, is a cultural object that produces knowledge. This was the real draw for me and the pleasure.

Lenore: In some of your work, Susan, you put your body in a state of precarity and at the same time you assume a position of power. I remember your project Helmbrechts walk, 1998-2003, (link: http://helmbrechtswalk.com) where you retraced the 225 mile path that women prisoners marched from a camp in Helmbrechts, Germany into occupied Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic). And more recently I saw the stills of your performance as Leda in your work Leda and the Swan, 2019 (link: https://susansilas.com/leda-and-the-swan-2019), of your naked body in a warehouse with a live swan. Do these projects relate to your personification of Medusa? Why Medusa now?

Susan: Helmbrechts walk marked a change for me in how I understood myself as an artist. My work had functioned up until that point as a kind of post-modern meta-commentary, but in Helmbrechts walk, I put my own body into the work, even though it is not seen in the frame. It was about an indexical representation of the march route of a group of women prisoners at the end of World War II, realized by putting my body into the same physical space that they had occupied 53 years before. It was also about giving a “voice” to the experience of women during the Holocaust, because with the exception of a few notable writers like Ida Fink and Charlotte Delbo, the entire history of the Holocaust had been written by white Western European men, although that has changed slightly since the fall of the Berlin wall and access to writings from the East, also primarily by white men. But this project marked an evolution for me, one where slowly, I became aware that my work was about embodiment and sentient being.

In my works of self-portraiture, I am to some degree the exemplar in an exploration of the meaning of the self and the transformation of that meaning over time. In Leda and the Swan, and in MEDUSA, there is some overlap in subject matter as both are dealing with mythological stories that had great staying power and have been represented in the arts for centuries, and in both cases my iteration of them is dealing with the aging female body, among other things. When you ask why I have chosen the Medusa now, aging is one of the reasons. I find the Medusa a curious icon for feminism. For French feminists in the 70s she stood for both female rage and the fear of female desire. For Primo Levi after the Second World War, she was the ultimate object of unspeakable horror. In fact, throughout history the perception of Medusa vacillates between one of horror and one representing the danger of female desire, two sides of the same coin it seems to me. She has also been hypothesized as “the representation of the unwatchability of one’s own death”. She was said to have been beautiful, but was cursed by another woman for a rape over which she had no control. Athena transformed her into abominable ugliness. In contemporary patriarchal culture, this is something like the transformation women undergo from youth, where they are seen as beautiful objects, to old age, when they are seen as useless and ugly. Yet with all this, she had the power to confer death simply with her gaze. In that way she signifies the perfect revenge on the scopophilic male gaze.

In Leda and the Swan our relationship to the animal world is part of the work, but so is the creation of a space in which the myth of rape/seduction is turned on its head because the swan, the rapist in our origin story, is completely, narcissistically involved in preening itself, showing no interest in me and because in any room with a human and an animal, the human is the presumed predator. And of course, in both MEDUSA and Leda and the Swan, I have adopted the subject position of the mythological character, looking at them from the inside out.

Lenore: Why did you use the medium of motion capture for MEDUSA?

Susan: The representation of the Medusa is presented by me in three media: as a motion capture video, as a three-dimensional sculpture, and as a series of photographic portraits. All three forms of representation are produced from the same source file, and that file is anchored in an iconic representation of me, based on a 17th century marble by the sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Lenore: Why Bernini? And what’s your objective in exploring three media? Is there any single medium that works best for you?

Susan: When I made my first digital sculpture I looked to classicism because I was interested in the way classicism had come to be understood as the representation of an ideal in Western culture (one that is now contested for a variety of legitimate reasons), but I also looked to painting and sculpture from the 16th and 17th centuries, a period when artists consciously re-engaged with classicism. Bernini’s ability to create the illusion of flesh from marble is probably what has always attracted me to him. And then he did sculpt the Medusa. From there it was an easy choice to adapt his head of snakes to my own. And of course, there is St. Theresa. There are not many sculptures depicting a woman coming, especially sited in a church. And he sculpted the mattress that the Sleeping Aphrodite rests on in the Louvre. So this exquisite antiquity sleeps on a bed that he made.

With respect to the medium: sculpture, photographic portraits and motion capture, each do separate things. But I am interested in the way they are related to one another through the data relay that occurs from the time of capture to the decision about how to output, since my photographs, sculpture, and motion capture are all derived from the same parent file.

Susan: You mentioned to me in conversation that you don’t specifically identify with the character of Circe but are rather interested in that moment when matriarchy, or at least a more equal symbolic representation of the relationship between the sexes is replaced by the patriarchal order. But I am also curious about your choice to represent Circe in the context of comedy. The two major forms of traditional drama are tragedy and comedy. The comedic often suggests a happy ending of sorts and yet here we are still stuck in patriarchy. So I am wondering how comedy both serves and shapes the story for you? Some literary critics have defined comedy as the realm in which the individual is open to and accepting of the world, while tragedy is the form in which the hero wants to bend the world, often unrealistically, to their own will. And this analysis sometimes stretches to become associated by gender with men generally associated with the wilful and unyielding characters standing on principle (Antigone a notable exception), while women are seen to care more about the health of the community and good resolutions. Thoughts?

Lenore: I don’t see comedy quite that way. I’ve been drawn to dark comedy and a certain kind of stupidity that is life. In film I think of Buñuel and Pasolini, in theater it’s Richard Foreman, The Wooster Group, all artists and directors I admired when I was starting out. There are two films by Pasolini that resonate for me, brilliant films. Uccellacci e Uccellini (The Hawks and the Sparrows) and Teorema (Theorem). We are not rational beings, we make stuff up to get along. The big myths are fabrications, they delude us, but this is what we have.

Lenore: Susan, remember our Zoom meeting a couple of weeks ago. It was so interesting to see how your digital enhancement of Medusa, the imposition of an image onto your face, was more frightening to me than any statue because that creature, Medusa, was live: the snakes were moving, and her—or your—yellow eyes flickered. I thought of theatrical tricks, the hallucinatory tricks, that ancient oracles played in their caves. But the yellow eyes were merely a virtual background, Zoom, virtuality in a pandemic, where we anticipate a neutral environment.

Susan: The avatar-like quality of the motion capture representation and the manner in which it feels remote but familiar echoes the current day relationship we have to mythology and the heroic language of antiquity. It’s part of our common cultural inheritance in the West, but the heroic scale is somewhat remote for us. Funny that the video had that effect over Zoom.

Susan: You asked me why I chose motion capture as a medium. I wonder why you chose film?

Lenore: Circe was filmed as a document, a recording of something that actually happened: a walk, a derivé, a rehearsal for a play. It was an improbable spectacle shot on the streets of Genoa rather than a representation of a narrative. In the editing though, the story of the Homeric character Circe took precedence, so there are really two sides to this project, one is documentary and the other has aspects of narrative cinema. The character Circe is wryly funny, gently deceitful and the Genovese and Spanish actors we recruited are meant to be clueless from beginning to end.

But there is more to it. I’ve been reading Giuliana Bruno’s Atlas of Emotion: Journeys in Art, Architecture and Film. She writes about the dynamic confluence of film, body, architecture : “A haptic dynamics, a narrative space that is intersubjective, for it is a complex of foci-sexual mobilities. Unravelling a sequence of views, the architectural-filmic ensemble writes concrete maps.”

Susan: I wonder if you could elaborate on this quote from Bruno, especially about foci-sexual mobilities and what you think she means by that, as I find it hard to parse, and if you could touch on whether part of you choice of film as a medium has to do with generating pathos?

Lenore: First pathos. Pathos in the sense of suffering, no. It’s a screwball comedy, make no mistake. When I think back everything I’ve made for decades has an element of comedy. As for foci-sexual mobilities in the work of Bruno I’ll try to unpack some of her thoughts. Bruno talks about motion within a film, about charting the motion of emotion, the landscape which the motion picture itself has turned into an art of mapping. She describes the relation of the moving image to other visual sites, its bond to architecture, travel, and the history of art, as well as its connection to the art of memory; using our bodies to sense their own movement in the formation of space.

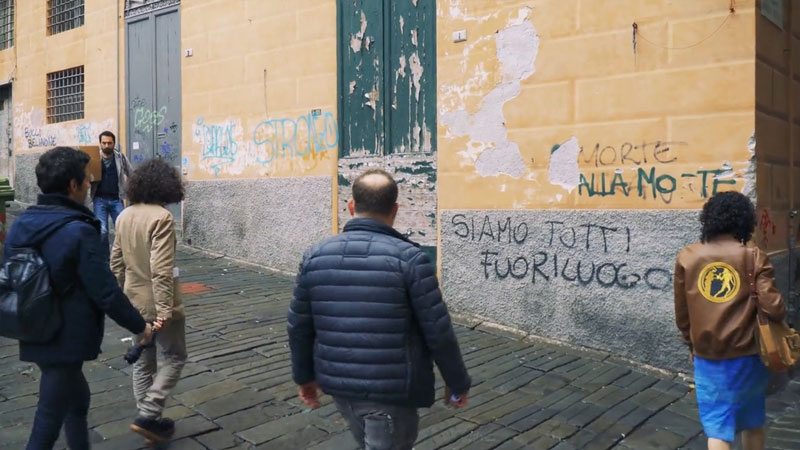

We filmed in the Carrugi and in the Ligurian Apennines. But the first scene takes place in Porto Antico where migrants congregate. A few minutes into the film the characters turn a corner and view a graffiti filled wall: “Morta All Morta — Simao Tutti Fuoricuogo” (“Death to Death. We are all out of place”), a stark reference to the Genovese migrant community and the crisis of global dislocation. Grosz calls this kind of journey “a physical displacement whose itinerary binds the city voyage to film, weaving motion through a culturally conceived space.”

The film is about losing your way, prone to misdirection, foolishness, the actors mimicking Odysseus’s crew are unsurprisingly indifferent to the dire graffiti: “Death to Death”. Interesting to note that Greek society around the time of Homer was in a similar kind of upheaval as ours is now. The word xenia means hospitality and friendship; the cognate word xenon means stranger and is at the root of xenophobia.